The climate we live in and experience through our journeys, observations and human connections with the natural world is ever transforming.

Artworks created in a variety of media by 14 diverse visual artists have been selected for exhibition. In addition to a shared connection to Wisconsin, each artist has also lived and worked in various parts of the world such as Canada, Southeast Asia, Mexico and other regions of the United States. This includes the vision of indigenous artists and their relationship to the land and the environment.

Up to 50 works in various mediums will be exhibited, allowing for many thematic interpretations and experience to surface. The public will have the opportunity to interact with the work as an observer and/or as an active participant through their involvement in the corresponding educational programming.

Earth, Wind, Fire, Water, Sky: Climate Transformed

January 26 to May 14, 2023

Opening Reception: January 28, 2023, 2 to 4 PM

Closing Reception: May 6th, 2023, 2 to 4 PM

Curator’s talk at 2:30pm

In content, the artwork explores the human relationship to the landscape and nature made evident through agricultural use, migration, habitat change, warming temperatures, wildfire, drought and heavy rains. The work will draw the viewer in to reflect upon not only the beauty of the natural world but also question our commitment to sustainability and to a reciprocal relationship which strengthens the exchange of resources and knowledge. The exhibit will engage and include multiple perspectives asking viewers to participate as better global citizens as well as offer them resilience and hope to strengthen their bond with the earth at this crucial point in history.

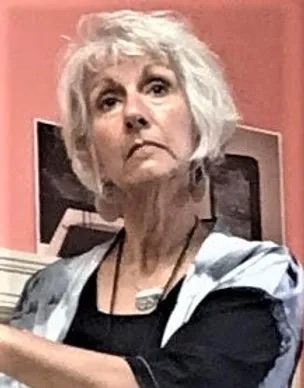

This Exhibition is curated by guest curator and artist Christine Buth Furness.

Climate Transformed Discussion Panel

Date: April 6, 2023, 4 to 5:30pm

The panel artists will discuss how their work reflects the human relationship to the environment and the natural world and how it offers resilience and hope in this time of climate change and transformation. They will also each give a brief presentation on their research, aesthetic, and process. To round out the panel, we’ve invited Professor of Environmental Science at Concordia University Bretta Speck, Ph.D to discuss the important role artists play in environmental education.

The panel includes artists Helen Klebesadel, Colette Odya Smith, Jan Mirenda Smith, Tori Tasch, Rina Yoon, and guest curator Christine Buth-Furness. Also featured is Bretta Speck, Ph.D. Professor of Environmental Science at Concordia University. This panel will be moderated by Cedarburg Art Museum curator Samantha Michalski.

Meet the Artist

Hannah O’Hare Bennet

Madison, WI

The concept of my work, supported by rigorous study and research, almost always involves human relationship to the landscape and nature, which is what agriculture is.

In my opinion, a lot of my work has to do with climate transformation because it is material that has been impacted by natural forces, especially the paper pieces, which are born in water.

The overall theme of the work in this show focuses on the receding of water and on things that are revealed after the water goes. It’s pretty perfect that I work with handmade paper and dyes and pigments, which involve lots of water before the final product is revealed. Floods and droughts have been a preoccupation for me for my whole life, because the farm I grew up on was in a flood plain. At the same time there was often drought in the summer. This preoccupation has only gotten more pronounced as the world climate has become more unstable.

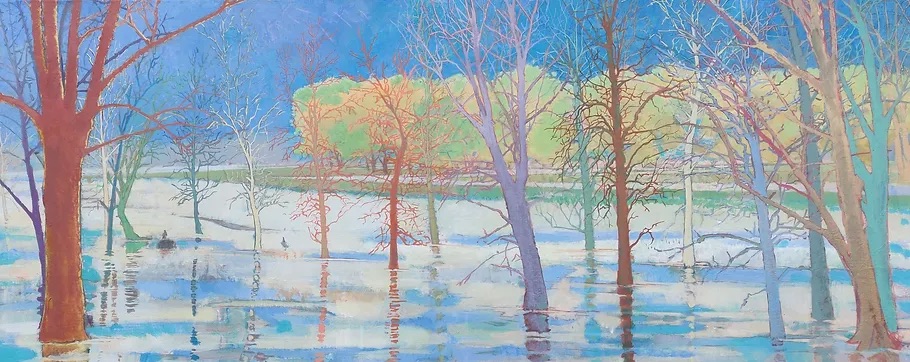

For me the landscape is the most accessible subject of the natural world. It has shaped our understanding of visual order. Our ancestors learned to read the landscape for survival, recognizing weather patterns for planting farm fields. I am fascinated by our ever shifting relationship to the horizon: that elusive edge of our planet. I use a painting knife as my primary tool to create a textured surface that describes the vast color experience of a landscape from afar but up close supports the objective nature of paint.

Looking into water, what do you see?

Reflection of clouds, and the blue of the sky.

Look again, look through, can you see?

Moving weeds and tiny fish and shimmers of light.

Water brings memories of childhood when the sandy bottom was smooth.

When you might see tiny fish swimming amongst the floating weeds.

The memories of looking out over clear water

or searching it’s depth.

What peace.

I paint these memories of water.

How I pray that the future holds these kind of memories for other children.

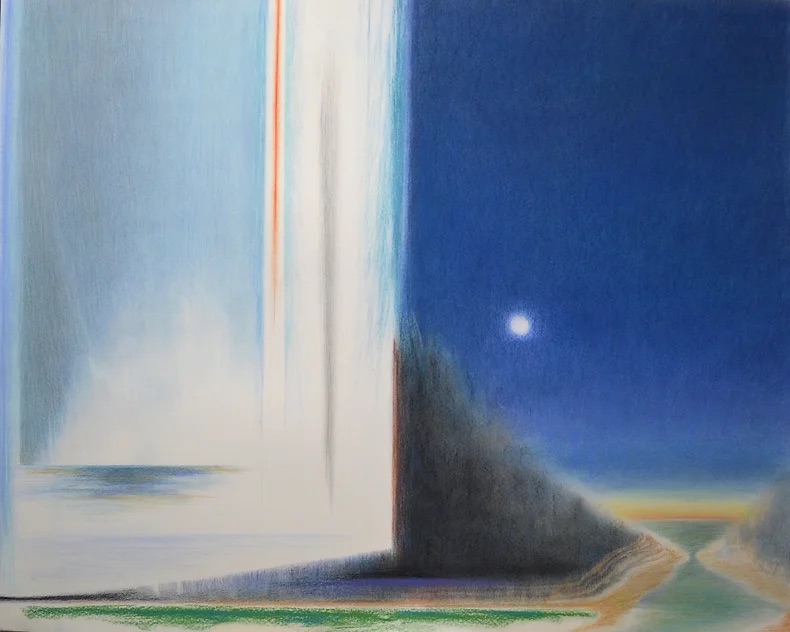

I divide my time between two studios. The main studio is in the land of great freshwater wealth in southeastern Wisconsin, and the other, inhabited during the winter months, is in northern California next to an oak forest at the base of Hood Mountain in the Sonoma Valley. This is a land of great majestic beauty, but suffering from drought and the consequences of wildfire.

“I Carry Two Landscapes With Me Wherever I Go” is an image divided in half with the left side suggesting a cascade of water falling and the right side representing a moonlit sky above a receding lake bed. The experience of living in and observing two ever changing landscapes is a personal journey taken with the goal of becoming a better citizen in the natural environment. My paintings and drawings suggest a human presence in an environment and evoke an emotional response. They are abstracted portraits of places experienced, spaces navigated and those imagined.

I am honored to be the guest curator for the Cedarburg Art Museum exhibition, “Earth Wind Fire Water Sky: Climate Transformed.” This exhibition allows connection, encourages questions, inspires responses and maintains hope.

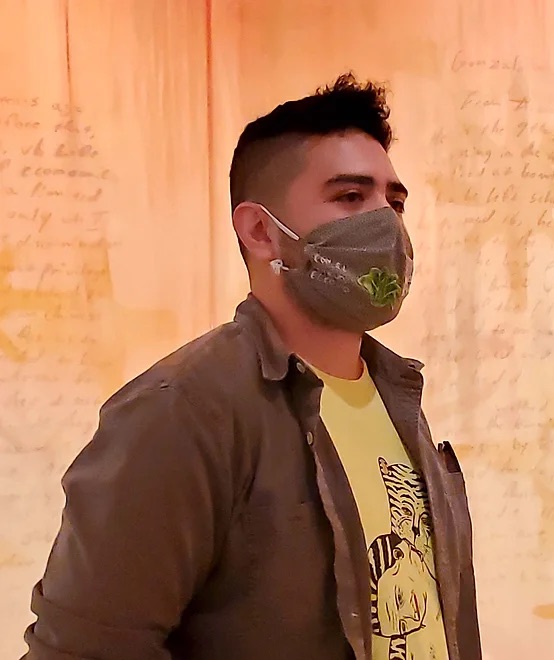

Jenie Gao (she/they) is a full-time artist, creative director, and entrepreneur. Her arts practice is based in printmaking, public art, social practice, and storytelling. She also has a niche consulting in equitable best practices and ethics for cultural organizations and the public sector. She strives to create records and claim space for resilient, diverse stories.

Jenie pulls from personal experiences as a second generation Taiwanese-Chinese American woman who grew up in rural Kansas, who worked their way into unexpected roles in the corporate world and beyond. Prior to founding her business, Jenie worked in the arts, public education, and lean manufacturing. Through her interdisciplinary work, Jenie advocates for equity for artists, fair pay for labor, and building equitable communities that work better for everyone. She has hired and mentored 24 paid interns and apprentices through her apprenticeship program at Jenie Gao Studio. She has been in business full-time for eight years and ran a 1,700 square foot art studio in Teejop (Madison, Wisconsin) until summer 2021 when she relocated to Vancouver, BC, Canada, where she is currently developing her graduate research on ethics in the arts, with special attention to BIPOC women and femmes’ labor and community impact as compared to their representation in the field.

I believe the fact of making art can be an act of self-determination and empowerment. My paintings examine how in re-claiming, revisioning and remembering ourselves as whole people, we bring our art, our action, and our voices to the world. We must be able to imagine the world we desire to live within in order to achieve it. In our creative work it is important that we notice and examine how awareness occurs on the path to finding a creative and critical voice. When we recognize that our place in the world is a part of larger social patterns, we can start to change those patterns to create the world we desire to live in.

Helen Klebesadel partnered with watercolorist Mary Kay Neumann to create a Collaborative Art and Climate Justice Exhibition and Project called The Flowers are Burning.

These six new works all deal with the ideas of climate change. Subtleties abound in the works. My choices in color use represent the following – although one can find many more ideas as one looks deeper into the challenges the environment faces. The grey represents the ideas (and facts) of pollution: smog, tailpipes, smokestacks, factory exhaust and more. The oranges represent the beautifully rich skies at sunrise and sunset as wildfires across the country and world burn. Gorgeous visually to see on the horizon from a far but devastating when it is right up close. My choice of the greens represent the pollution of our large and small waterways, rivers, lakes, and oceans. From the chemicals poured into the plastics and other garbage that has collected over the decades. Finally, the toned down reds of the burning of cities.

There is more to pollution and climate change than just what happens in the wilderness. The burning of the cities can be seen as the literal architecture being consumed but it can also be seen as the streets, the sewers, the lots and decay of buildings. Of course there is more. The underlying painting is taken from the sunrise of my own neighborhood and commute to work. Looking out at the beauty of the eastern horizon as the sun breaks it and casts the oranges and blues is a beautiful beginning to my days. From there I cast a number of light blue glazes over the top of the sky, blocking out the brushwork and beauty of the under-painting. The white-blue line that chases and builds up the outline of the shapes is from the same white-blue of the glaze, a coarse sand texture has been added to that and some of the colors within the shapes as well. A texture of contamination of the surface.

Finally, (and there is more – there is always more) the framing – finishing up the use of wood from other frames and constructions so that I can maximize the use use of the materials, I allow a gap between the back edge of the frame and the wall so that one can see clearly the colors of the under-painting without the haze and glaze over top. Some have pointed out that they see other things in the forms. I agree. Just like the clouds and the shapes in the sky, one can see what they will in the clouds.”

In my practice, I examine both human and animal migration as metaphors for one another. Migration—the ability to move freely in search of our fullest and best selves—is a fundamental right. My work raises awareness of the dire need to protect both migrants and the animal species that depend on migratory routes for survival.

Through my work, I direct attention to these complex issues within the scope of displacement. To de-stigmatize migration, I take a multimedia approach realized through the metaphors as symbols and icons to identify historical precedent. The work embodies an emotional sense of realities of human displacement as well as the routes animals depend on for long-distance movement for survival.

We are navigators, together we take paths to find solidarity with the promise for a better life. In our journey I believe we can help shape the dialogue around migration while removing barriers of division and promoting compassion and humanity.

“We are only killing ourselves,” replied artist Berenice D’Vorzon to a question regarding the effects of pollution on the environment. I was with a group of artists visiting her studio which was filled with her nature-inspired paintings. Of all the artists’ quotes I’ve heard during my life, that one stuck.

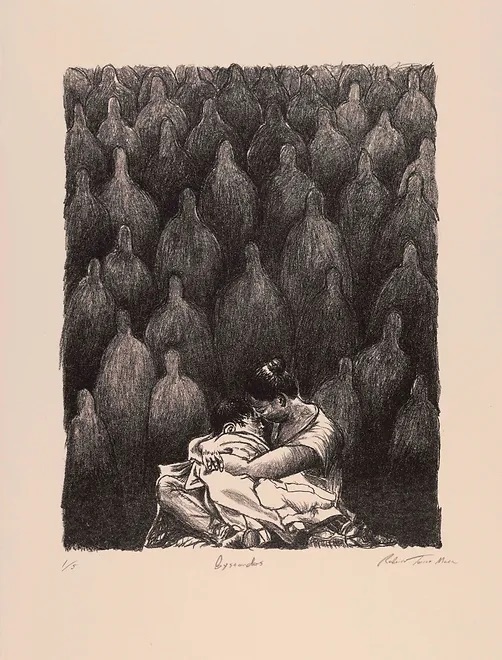

In response to this exhibition’s theme, an image that strikes me the most is the sense of being surrounded by dead trees. A neighbor first brought this to my attention when he asked if I noticed all the dead trees in SE Wisconsin. That was over 20 years ago. I started noticing that there are dead stands all over the U.S. And not just a few. Many seem to be the result of invasive insects brought in through international trade. But that overlooks other consequences of our changing environment: lowering water tables, worsening air quality, and warming temperatures. Personally, it’s a haunting talisman. “Luminescent Trees” is part of a series of works exploring this idea.

“Norris Basin” is more of a direct study of wildfire smoke. As an artist who begins much of my work plein air, I created this study on location in the Norris Geyser Basin in Yellowstone National Park in August 2020. In hindsight, I was fortunate to have been able to capture this much of the mountains that overlook the Basin. It was only a day or two later that all vistas disappeared into an eerie, and unhealthy to breathe, mist of smoke that enveloped the Park. It’s hard not to feel that this might be a future for all of us

The driving force behind this work is my interest in finding and amplifying the beauty and mystery that exists quietly all around us. Rocks, foliage, and especially water are my subject matter. Through them, my purpose is to explore realities that are both obvious and hidden. This dual interest has developed into the creation of images that are intentionally both representational and abstract.

I often obscure the customary references of horizon and atmospheric perspective usually found in landscape paintings. By doing this, easy identification of the scene is downplayed. Context and scale become malleable. This allows a broader range of interpretations and frees me to move beyond the literal. Adding to this ambiguity, I often mix reflected imagery with solid forms, begging the question of what is ‘real’ and what is illusory.

I invite the viewer to ponder with me the challenges presented by being essentially spiritual beings living in a material world. Just what is our relationship with nature? What is our responsibility? What do we make of the evanescent colors and forms we see? What lessons are we being asked to learn? Each of us brings a unique perspective and appreciation to these explorations.

I am a Milwaukee native now living in Wauwatosa, and have been pursuing my love affair with pastels for nearly 30 years. I received my degree in Fine Art and Humanities at Macalister College in St. Paul, MN and taught art in public schools and raised two children.

My work has been exhibited widely in the US and internationally in France, Germany, and China, winning many prestigious awards and being included in public, private and corporate collections. My professional recognitions include designations as a Master Pastellist of le Societe des Pastellistes de France, Eminent Pastelist and Masters Circle Member of IAPS – The International Association of Pastel Societies, Master Pastelist of PSA – Pastel Society of America, and Distinguished Pastelist PSNM – Pastel Society of New Mexico. I have been published in 3 books on pastels and abstraction, and been featured multiple times in The Pastel Journal, American Artist, and Pratique des Arts magazines.

I teach workshops, offers critiques, and have juried and judged many exhibitions and written for The Pastel Journal and American Artist Magazines.

Closer to home, I am a member of WVA-Wisconsin Visual Artists, WPA-Wisconsin Pastel Artists, and LMA–the League of Milwaukee Artists. My work has hung at MOWA–The Museum of Wisconsin Art, the Cedarburg Cultural Center, the Charles Allis Art Museum, the Anderson Art Center in Kenosha, and the Haggerty Museum at Marquette University, among other venues. I enjoy the mutual support and camaraderie of my artist communities, as we share and learn from each other. I offer these paintings from my heart and hope they speak to yours.

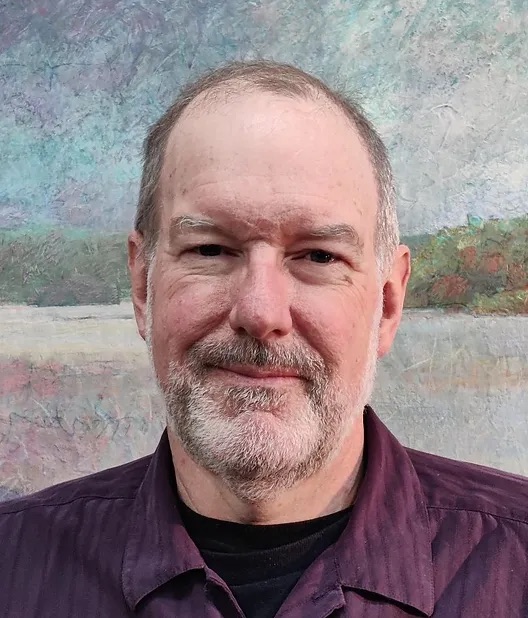

As an artist passionate about impact, I want my work to resonate with a viewer as a call to action. My hope is that the work creates awareness and serves as a catalyst for change, presenting an opportunity for positive redirection.

My recent work evolved during the early stages of the pandemic. The world was not only confronted with a deadly virus, but our days were consumed by extraordinary events. From this period, the Storming Series emerged using dramatic landscapes from photos I have taken to create pastel and watercolor images that wrestled with the changing atmospheric conditions of our time through climate change.

My studio work consists of both watercolor and pastel, focusing on landscapes, sometimes painted plein air and more often worked from photos I have taken outdoors. I use landscape as a metaphor to mark periods in time, episodes, transitions, change and emotional impact.

As my work evolves, I hope to not only draw attention to these issues, but encourage viewers to act in simple, imaginative ways to solve problems.

In my previous career, I was a museum professional and found that exhibits can provide learning opportunities, resulting in new information to visitors. By creating my own work with the hope to instill new awareness, I want to evoke a response in the viewer and provide a fresh perspective. By combining these two practices, I can bring harmony between my previous profession and my current practice in painting.

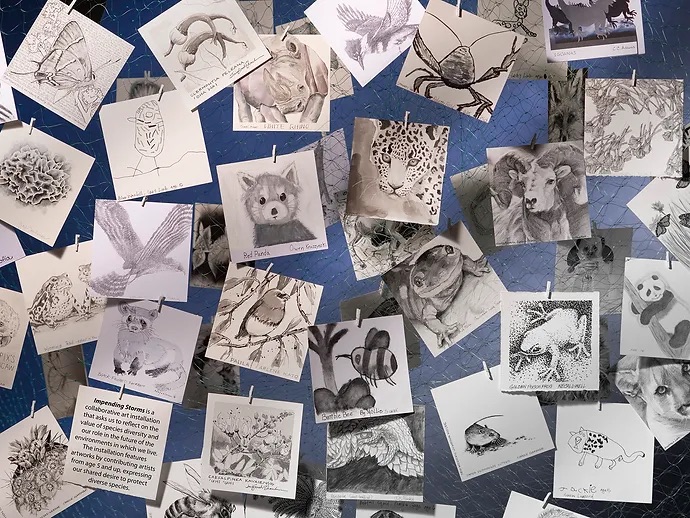

The purpose in creating this art installation is to put a spotlight on the reality of the impending dangers of significant loss of species and biodiversity, and by inference, the dangers looming over our biosphere. The human-caused environmental change has already brought about not just the loss of biodiversity, but also the climate change, the rise of oceans, the loss of habitable land for endangered species, the wildfires, the floods, the mass emigration, and the pandemics. These problems plaguing the world stem from extreme politics, economic demands, unwise and inconsistent policies, and international conflicts. By involving many artists, including school children, wishing to make drawings expressing animals and plants that are caught in the “fishnet” of human design it is our wish that this message will be carried to wider audiences so our work can join global efforts to regain the health of our fragile biosphere. We offer this installation as an invitation to reflect on the losses our planet has suffered, what role we have had in this, and how we might work to change the current path.

For more information on Blue Marble Art Collective’s traveling installation, see HERE.

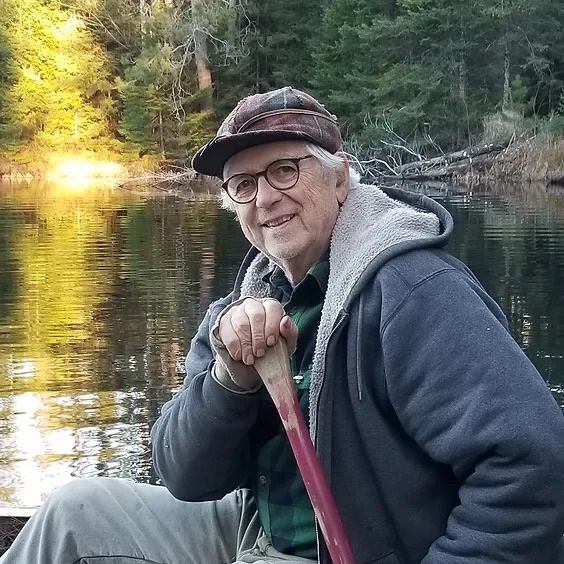

Tom Uttech is one of the leading landscape painters working in the United States. His work is inspired by the woods of Northern Wisconsin and the Quetico Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada, where the lakes, forests, and wildlife are untouched by humans. His devotion to nature is apparent in each piece, as Uttech thoughtfully recreates what it feels like to be in those woods at dawn and dusk when the mystical characters of the forest come to life. Uttech’s use of Ojibwe titles enhances the sense of mystery and pays homage to Native American culture.

The artist has been represented by the Tory Folliard Gallery since 1992.

Extreme heat, high wind, years of drought. From California coast to the southwest, the country is on fire. In the past ten years, hundreds of thousands of acres have burnt and are burning. In June 2020, I spent a month in Tucson, Arizona during the Bighorn fire, which devoured 120,000 acres of Santa Catalina Mountains. Ready to evacuate at a moment’s notice, we watched the mountain glowing red at night, nervously waiting for the monsoon season to start. It’s one thing to read about a catastrophic wildfire in Apple’s newsfeed. It’s another thing to witness one in close proximity. Two years later, I visited one of the burn sites. Life continues even where the fire had blazed through not too long ago. You can see new growth, shrubs and wild flowers blooming in stark contrast to charred and blackened mesquite and pine trees. In many cases, the heat of the blaze produced a gallery of grotesque forms: twisted trunks and warped branches and detached outer barks. Charred, naked, hollowed, the trees remain standing, as if they are there to tell us what they witnessed, hanging onto the memory.

I gathered some of the remains, brought them to the studio, and began cleaning off the soot and ashes. To me this act of tending was more like a conversation I had with the trees that may not have survived the fire but still had a story to tell. As I cleaned and added hand-coiled paper, I felt connected to the beauty, horror, and resilience of nature. The aftereffects of wildfires are rarely part of their story, which ordinarily focuses on the spectacular blazes that ravage large tracks of parched wilderness. Windblown flames, record heat, Hotshot crews—these are the storylines. What is there to say about burn scars themselves? Whether forests will be resilient to things like wildfires and climate change is a huge question. A lot depends on the recovery time of areas damaged by severe burns, which can be long. A piece of forest with moderate harm might show robust signs of recovery a decade from now. A really bad burn area might not recover for 100 years. As I conceive it here, the process of healing begins now with a conversation with the remains of fire.

Recommended Readings

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass and Gathering Moss

Janine Benyus, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature

Dan Egan, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes

Erica Giles, Water Always Wins